The most famous native-born artist son of the southern Spanish city of Cordoba is Julio Romero de Torres. Although, in his art, the beauty of his city gets a place, its particular focus is on that of its women. In one of his particularly striking works, Alegrias, such beautiful women, in companionship with an intensely focused guitar player in the corner, almost seem to bring the rhythm and movement of the famed flamenco of Andalusia to the obviously silent and static art of a painted canvas.

A greater work by Torres is his 1913 “The Poem of Cordoba.” He uses seven panels in the form of a medieval altarpiece to depict the long history of this most fascinating of cities. Each panel, with its own unique historical background details, is dominated by a striking Andalusian woman who personifies the spirit of a famous man from the city’s glorious past. The one that depicts Cordoba in the centuries-long interval between the Christian rule of the Visigoths and the Reconquest features the Jewish philosopher Maimonides, a famous native of the city. I take umbrage at this, yet in doing so, no insult is meant to the memory of Maimonides, who is indisputably one of the most important figures in Jewish philosophy. It is simply that Maimonides represents a minority, albeit a significant one, in the Cordoba of the time, whose ruling class and dominant population was Muslim, and that in terms of famous philosophers, the Cordoban Muslim philosopher Ibn Rushd, or Averroes, is of even greater historical significance than Maimonides.

Thus, the selection by Torres of a Jew to represent medieval Cordoba cannot but be viewed as a deliberate snub to the Islamic civilization of that time. However, viewed differently, it is perhaps a warped compliment, for it seems that Torres was disturbed by this civilization to such a degree that he was unable, even at the distance of centuries since Christian rule had been re-established, to come to terms with it, and wished to delete it on canvas effectively. But the truth is he cannot delete the fact that the golden age of this city took place under Islam.

Indeed, reminders of it are still present there, particularly in its most beautiful building. Although this now officially forms part of a cathedral, the former Great Mosque of Cordoba is one of the architectural wonders of the world. Its huge prayer hall, with its evenly spaced pillars connected by horseshoe-shaped arches, is a geometrically aesthetic delight. The figure who founded this mosque clearly did not lack artistic taste, although it should be pointed out that the original mosque of Emir Abdurrahman I is half the size of what it is today, his successors having enlarged it.

The Emir Abdurrahman I (731-788), ruler of al-Andalus in Iberia (756-788), whose famous palm poem is the focus of this piece, established a polity that, while it only directly lasted through two successors, had such a profound impact on the life and culture of al-Andalus that it literally continued up to the final reconquest of the peninsula by the Spanish in that most evocative of dates, 1492, and has left its mark on subsequent Spain as well.

For a figure who would have such an impact in Iberia, it is interesting that he may never have felt at home there. Abdurrahman went into exile from Iberia for fear of his life. To understand how this is the case, it is necessary to look at the larger canvas of early Islamic history.

Abbasid revolution

In Ramadan last year, my piece on Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, the seventh in my “Famous Travelers to Türkiye” series, touched upon the early Islamic Caliphate. This piece is intended as something of a Ramadan-inspired sequel to that one. Here, the Caliph Mu’awiyah (661-80) is once again significant, but this time, it is for his role as caliph and not for his wish to conquer the Byzantine Empire. Mu’awiyah is the fifth caliph, the four prior to him all being companions of the Prophet Muhammad and extolled for their piety, thus being collectively known by Sunni Muslims as the Rashidun, meaning the “rightly guided ones.” Mu’awiyah, however, marks a change in the nature of the caliphate. For under Mu’awiyah, the caliphate becomes dynastic – he nominates his son Yazid to succeed him – and the piety of the original caliphs fails to be maintained. Symbolically, the political capital of Islam has also been moved from the Holy City of Medina to the relatively recently conquered Damascus in Syria.

It is also noteworthy that while there are a total of 13 Umayyad caliphs, their caliphate did not even last a century. They were overthrown in a revolution in 749, when Abdurrahman, a member of the Umayyad family, was still only a teenager. With hindsight, the Umayyads can be seen to have brought about their own destruction. Although they ruled over the expanding Islamic empire, they deemphasized the core principle of Islam, which is the unity and equality of its body of believers, ruling instead through a form of Arab chauvinism. However, inimical to the religion this may have been, in terms of realpolitik, this perhaps did not matter too much at the establishment of the dynasty when being Arab and Muslim was still virtually, though not completely, synonymous. However, as time passed and the religious polity expanded, the number of non-Arab, especially Iranian converts to Islam grew in size and strength. And these new Muslims were understandably discontented to remain second-class when they had enthusiastically embraced an egalitarian faith.

There was also a geographic issue with the Umayyads. Their capital, Damascus, lay close to the border with the Byzantine Empire. Yet, despite Umayyad attacks upon Byzantium, including the 674 siege of Constantinople in which Abu Ayyub died, the heartlands and capital of Byzantium were not to fall to the Umayyads but rather to the Turks some centuries later. Where Islam was then able to expand was to the east – among the aforementioned Iranians in particular – and this meant that Damascus found itself at a greater and greater distance from the dynamic expansion taking place.

Matters came to a head in the eastern region of the caliphate known as Khorasan, traditionally part of the Iranian world. Here, as the historian Hugh Kennedy notes, “There was considerable integration between Arab and non-Arab.” A high proportion of its population were converts, and this region, having turned against the Umayyads, looked instead at the descendants of the prophet’s uncle Abbas, known as the Abbasids and based in what is now Jordan, for new leadership. As Kennedy notes, “The Abbasid message … seems to have emphasized the equality of all Muslims regardless of race and ancestry,” and the message appeared genuine in that its most significant proponent in Khorasan was Abu Muslim, who had been a slave but was granted freedom by the Abbasid family.

The uprising against the Umayyads in Khorasan succeeded, while the Abbasids took control of Kufa in Iraq. In this city, Abu’l Abbas was proclaimed the first Abbasid Caliph with the name al-Saffah. Due to special cohesion within the family, the Abbasid Revolution was a success and, as Kennedy reveals, “Abbasid rule was established and accepted by most of the Muslim community,” due in part to a successful attempt by the Abbasids to “win over” ex-supporters of the Umayyads. However, Kennedy also reveals that “this general reconciliation” did not extend to “the members of the Umayyad family itself.” Rather, “all the prominent Umayyads were hunted down and many of them executed” by the new Abbasid governor of Syria, with “only one” who was “a grandson of the” tenth Umayyad Caliph Hisham (724-743) “escaping to join supporters in Muslim Spain where he founded a long-lived and successful branch of the dynasty as the western ends of the Islamic world.”

It is noteworthy that Albert Hourani makes this similar comment: After the “Abbasid revolution, a member of the Umayyad family could take refuge in Spain and found supporters there. A new Umayyad dynasty was created and ruled for almost three hundred years.”

Abdurrahman, his rule in Iberia

This member of the Umayyad family is, of course, Abdurrahman, who was thenceforth known as al-Dakhil, or the immigrant. However, what is of interest here is that Kennedy and Hourani, with their focus on the heartlands of Islam, imply with their concise paragraphs that for Abdurrahman, once he managed to reach Iberia, there was a smooth transition. That is the way it is often viewed – that the crisis in Abdurrahman’s life was brief and he literally escaped it by putting the bloodshed of Syria behind him. Yet, in truth, Abdurrahman did not find himself in an idyllic outpost of the former Umayyad dominions full of loyal citizens eager to embrace a member of the fallen family as one of their own, but rather a land marked by what the historian Richard Fletcher calls “hugely complicated and messy faction-fighting” and in which Abdurrahman was compelled to take part. Thus, the violence that sent him into exile was not left behind him but rather also marked his career for nearly three decades, during which he slowly but surely established his domination.

Abdurrahman the man, his famous poem

The picture so far formed of Abdurrahman is that of a survivor of the massacre of his family and an iron-willed exile willing to forge his own fate in a new land. It may, therefore, be surprising that he was also a man of particular sensitivity, for he was also a poet. And the poem that he is most famous for is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a poem of exile. In the version used by the historian Gary Paul Nabhan, it runs like this:

“A palm tree stands in the middle of Rusafa,

Born in the West, far from the land of palms.

I said to it: ‘How like me you are, far away and in exile!

In long separation from family and friends

You have sprung from soil in which you are a stranger;

And I, like you, am far from home.”

Poem’s meaning, significance

The general meaning is very accessible. It is about a man in exile who, by addressing a palm tree, whose fellowship to him is in its also being a non-native species, can share his sense of a lost past and deep personal displacement.

With what has been made clear about Abdurrahman, it is impossible that the poem was not composed in al-Andalus. The details of the “long separation of family and friends” and the idea of being “in exile” and “far from home” are inexplicable if this does not refer to Abdurrahman in Iberia. This is supported by the fact that al-Andalus is in the extreme “West” of the Islamic world and that, as such, it was “far from the land of palms.”

Yet its reference to Rusafa can, at first, be a little confusing. If one looks up the name today, it will be seen that it refers to an ancient site in Syria particularly favored by the Caliph Hisham, Abdurrahman’s grandfather. Here, Hisham built palaces and an especially famous garden. It was a site that Abdurrahman knew well in his boyhood and felt a deep attachment to. Yet, as the poem is set in al-Andalus, Abdurrahman cannot have been referring to this Rusafa.

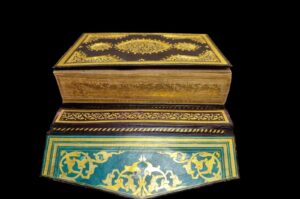

And he was not, for there was another Rusafa, one created by Abdurrahman in his newfound home. The emir, as the poem suggests, was particularly nostalgic. This inspired him to carry out a building program of his own. As Nabhan reveals, “outside of Cordoba,” Abdurrahman “constructed a replica of the gardens and palace of Rusafa, the place from which he had fled just as he had come of age.” Nabhan also clarifies that Abdurrahman constructed all of this for emotional reasons, as in his garden there, “he hoped to grow a little bit of paradise to salve the wounds of the last few years.”

In planting his nostalgic garden, Abdurrahman was given a highly unexpected but particularly appropriate gift. Abdurrahman came to discover that other members of his family, including a son, had survived the general massacre of his family. He sent a trusted emissary to go to Syria and bring them to him. Meeting with Abdurrahman’s relatives, this emissary could only persuade one of the two sisters of the emir to travel back with him. However, this other, knowing the temperament of her brother, got the emissary to go to the abandoned original Rusafa palace and collect whatever he could from the now untended gardens. As Nabhan relates, this emissary “clandestinely dug up a few young date palms and grabbed several pomegranate fruits that had somehow survived.” These were then brought to Cordoba in the company of Abdurrahman’s rescued relatives.

From these gifs, the delighted Abdurrahman was able to oversee the creation of the first pomegranate orchard in Iberia, and it is now also clear how the palm tree in the poem found itself “far from the land of palms.”

The poem of Abdurrahman refers to a specific place and was brought about through specific circumstances. However, it has a spirit in which any who find themselves displaced may find an echo of support, much as, indeed, Abdurrahman finds from his palm tree within the poem. The poem was known by the Argentinian writer and poet Jorge Luis Borges, who references it in one of his brilliant short stories, which is based on Averroes. Ironically, for Borges’ Averroes, the placing of nostalgia works in reverse, even if its spirit is the same. Averroes also becomes an exile and Borges’ version of him has him declaiming Abdurrahman’s poem “this singular benefit of poetry: words composed by a king who longed for the Orient served me, exiled in Africa, to express my nostalgia for Spain.”

Finally, in dealing with the legacy of Abdurrahman, what is particularly notable is that this emir, who may not have been unable to escape nostalgia for his youth, actually founded the dynasty of what would be the most forward-looking state in Europe in the Middle Ages. For under Abdurrahman and his successors, Cordoba would become what Nabhan notes was “Europe’s most sophisticated center for intercontinental trade, translation, and education; research in the arts, sciences, and letters; and agricultural, horticultural and medicinal plant experimentation.” Hence Nabhan also asserts that the emir who “spent the remaining years of his life cultivating” the “soil” and the “society” of al-Andalus, left a legacy in which “both would bear fruit on an unprecedented scale.”

Be First to Comment