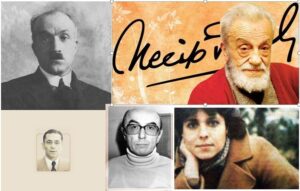

“If you want to be free, be it,” Soviet film director Sergei Parajanov once said. Now, as Parajanov’s 100th birthday is celebrated posthumously 34 years after his death, his legacy as a film director is overshadowed by his iconic status as a dissident artist and Soviet political prisoner during the mid-1970s.

Despite the vast interest in Parajanov, there has been little examination of his interest in Azerbaijan. The topic is also taboo in Armenia. Parajanov, though, did not just spiral from nowhere. His background and life in the South Caucasus played a major role in shaping his view of the world. Azerbaijani culture also had a significant influence on him, expressed, in part, by his desire to make a film about Ashiq Garib.

Sergei Parajanov and Dodo Abashidze’s 1988 drama, Ashik Kerib, is an extravagant art film overflowing with all styles of earthly delights. Parajanov’s final feature film crowns Russian writer Mikhail Lermontov’s obscure interpretation of star-crossed Caucasian lovers.

The tender paradigm in Parajanov’s previous films like “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” (1965) and his acclaimed “The Colour of Pomegranates” (1969) reaches its zenith here: By blending centuries-old rites with politically themed relics, Abashidze and Parajanov recreate a past beyond the bounds of the historical tale. If the tones of Azerbaijani culture are not your cup of tea, do not fear: such is the power of Parajanov’s filmography, a language of delicacy all can grasp.

According to Azerbaijani composer Javanshir Guliyev, who worked with Parajanov on Ashik Karib, the filmmaker had a soft spot for Azerbaijani mugham.

“He always carried an audio cassette with recordings of Alim Gasimov in his pocket, which made his eyes teary. But the most amazing thing is that Sergei Parajanov lived and worked in Baku for a whole month, just three months after the Sumgayit events of 1988. He stayed at the Azerbaijan Hotel, currently known as the Hyatt Regency,” Guliyev added.

One could say that Ashik Kerib was an odyssey into Parajanov’s own personal heart of guilty pleasure: his affection toward Azerbaijani culture. As his most personal film, which was dedicated to his close friend Andrei Tarkovsky, it was also his most cherished film, albeit by deliberate misdirection.

In Azerbaijani filmmaker Turkan Huseyn’s opinion, Parajanov saw the Caucasus as part of a world that is not yet nationalized and showed that “you can go beyond the boundaries and create your own visual language.”

“He was inspired by the cultures around him, creating scenes of folk figures tangled in the hustle of a city.”

While confronting Soviet censors, Parajanov managed to flow against the nationalist sentiments that ran in the Caucasus in his lifetime – just like another famed cosmopolitan before him, the 17th-century bard Sayat Nova, a mythical figure who also became a muse for Parajanov’s movie, the “Colour of Pomegranates.”

Eventually, Soviet authorities couldn’t tolerate Parajanov’s nonconformist stance and his sexual orientation. The film director was sentenced to five years in a labor camp on charges related to homosexuality and pornography, which were widely seen as politically motivated charges. The experience took a toll on his health, and he died of lung cancer in 1990 at the age of 66.

Film critic Haji Safarov notes that Parajanov was interested in ethnic codes embedded in memory and their resolution in cinema. “His films gain strength from self-awareness and appreciating the past with a different perspective,” Safarov says.

Today, Sergei Parajanov has entered popular consciousness as one of the great pioneers of modern cinema. The film director’s impact extends beyond the silver screen, inspiring subsequent directors and music icons like Madonna and Lady Gaga.

With provocative notions, bold cinematic decisions and enigmatic imagery, Parajanov forever transformed the cinema landscape, bestowing upon us some of the most recognizable characters and reflecting on life through the lens of authenticity. The combination of his visualization and brashness as an artist left a mark on the history of the medium, and cemented Parajanov’s legacy as a filmmaker who continues to inspire, provoke and exceed temporal boundaries.

Be First to Comment