Argentina is seeking to realign business relations with China, as bilateral trade with the Asian giant has opened up a $9.5 billion trade deficit, constricting the Latin American nation’s already strained economy.

From $2.3 billion in 2001 to $26 billion last year, Beijing has become the second-largest trade partner of Buenos Aires and has increased its footprint in the Argentine economy.

The total value of Sino-Argentine bilateral trade stood at $450 billion as of 2021.

In January, Argentina’s Foreign Minister Santiago Cafiero sought to address the trade imbalance and find ways to get equal footing in dealing with the world’s second-largest economy.

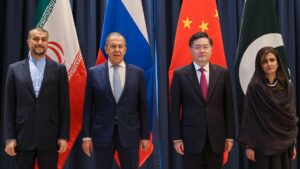

During a meeting with his Chinese counterpart Qin Gang, Cafiero reaffirmed the two nations’ strategic relationship and said it was vital “for our country to build together a more balanced and diversified bilateral trade, and to speed up the market opening processes for Argentine products”.

Over the past two decades, the two nations have solidified their partnership, enhancing trade and investment flows through joint venture projects in rail transport, energy, mining, infrastructure and public works. Argentina has also received numerous Chinese loans and investments in mining, oil and gas, hydropower, nuclear energy, solar energy, biodiesel, transportation, telecommunications and electronic sectors.

“Throughout the 21st century, China has become one of Argentina’s main trading partners. It is one of the three most important destinations for Argentine exports along with Brazil and the European Union,” says Luciano Moretti, a researcher at the Santa Fe-based National University of Litoral.

High export commodity prices marked this commercial relationship, with Argentina exporting agricultural produce – largely soybeans and their derivatives – and importing a range of manufactured goods, machinery and technologies from China.

Moretti says this created a trade balance that was initially favourable for Argentina but “eventually became a deficit”.

During his conversation with Gang, Cafiero also described it as “important” to advance with China financing infrastructure projects, something Chinese banks have not done since 2019.

While there has been success with Chinese investment in projects such as the Belgrano Cargas Railway and the Cauchari Solar projects in Argentina’s northern province of Jujuy, there have also been setbacks.

The construction of the Nestor Kirchner and Jorge Cepernic hydroelectric plants has faced pushback from environmentalists and the indigenous Mapuche people, who argue that development in Argentina’s southern province of Santa Cruz comes at the risk of impacting glaciers and biodiversity.

One joint nuclear energy project also appears to be facing difficulties. The potential construction of the Atucha III nuclear plant in Buenos Aires province – which uses a China-designed Hualong One reactor – seems to have hit a stumbling block over finances. Some reports suggest that the project’s future is “ambiguous”, with China committed to investing 85 percent of the cost, around $8 billion, while Argentina pushes for full investment.

However, there may be developments on the horizon.

Last year, as both nations celebrated 50 years of diplomatic relations, Argentine President Alberto Fernandez met President Xi Jinping in China and signed up for Beijing’s pet project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), to receive more than $23 billion in Chinese investments.

According to Moretti, China does not require nations to formally join the BRI to receive financing or investments, describing the BRI in Latin America as a “set of infrastructure projects that China had previously announced and that now seem to fall under the umbrella of this initiative”.

Amid Argentina’s deep economic crisis, Leandro Marcelo Bona, a researcher at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council and the National University of La Plata, says the BRI offers financing opportunities for infrastructure projects that global south nations cannot easily obtain. He notes benefits between China and its partners that are aimed at improving export capacity, productivity and trade, avoiding conditional financing offered by other credit institutions.

Moretti describes these Chinese loans and investments as adhering to a policy of non-intervention in the internal affairs of countries while its loans do not bring any “collateral of a political nature”.

“In this aspect, it differs, for now, from traditional international lenders, such as the IMF, which usually condition financial aid to regressive political and economic reforms in social and productive matters. This does not mean that China does not have a geopolitical and economic interest in its relationship with Argentina, nor that cooperation is free,” argues Moretti.

Critics, however, argue that cheap loans offered by China come at the risk of putting nations in Beijing’s “debt trap”.

To date, Argentina has received 36 commercial bank loans and 13 policy bank loans from China.

However, Bona suggests that Chinese banks are growing more cautious, mainly due to rising debts among partners in Africa, where Beijing has struggled to recuperate its money and is now undertaking debt-restricting negotiations.

“The other side of this financing is that it favours Chinese interests in obtaining foodstuffs and energy from countries of the South, reproducing an uneven development pattern, where added value is concentrated in China, and the regional countries continue to depend on commodity prices,” says Bona.

Amid the push to decarbonise and the world’s energy transition, lithium is one strategic economic area of cooperation. The white metal is a crucial resource for the burgeoning electric vehicle and electronic goods market, while South America’s Golden Triangle — made up of Argentina, Bolivia and Chile — is where 50 percent of the world’s lithium deposits are estimated to be located.

As China leads the way in refining and producing the resource, major firms like Jiangxi Ganfeng Lithium Co., Hanaq Group, Tsingshan Holding Group, and Zangge Mining Group Ltd are overseeing projects or have investments in Argentina.

In recent years, China has invested more in the lithium sector than other nations like the US, Canada and Australia. More than 42 percent of Argentina’s lithium exports head to China.

In January, both countries demonstrated their financial cooperation, formalising the expansion of a $5 billion currency swap to bolster Argentina’s hard-hit foreign currency reserves and to help with trade costs and debt repayments, notably with an IMF deal in place. The currency swap was first agreed upon in 2009 during former President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner’s tenure and continued under successive Argentine administrations.

Internationally, China has also backed Argentina’s push to become a member of BRICS, the five emerging bloc economies comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Fernandez noted how the bloc represents 42 percent of the global population and 24 percent of the world’s GDP, combined with new financial opportunities with the expansion of the New Development Bank (NDB) or the BRICS Development Bank.

Local newspaper Cronista suggests Argentina’s accession to BRICS would strengthen its economy, while Fernandez underscored “the prospect of coordinating policies that enhance the agenda of the countries of the Global South”.

In the future, analysts expect Argentina and China to deepen cooperation in commercial, financial and political terms but note potential challenges.

Amid the US and China’s geopolitical and commercial dispute, they say Argentina’s incorporation into the BRI did not go unnoticed in Washington.

“Let us remember that the US considers Latin America as its backyard and sees the entry of external powers into the continent as a possible threat to its security. Argentina must have enough manoeuvring capacity to avoid being trapped in this dispute between two great powers,” argues Moretti.

Bona underscores how the US perceives South America as “a ‘natural’ part of its sphere of influence (just as the China Sea is for the Asian giant)” and suggests that “it could lead to a more aggressive strategy by the US (which has greater potential through its financial channel) to avoid the growing weight of China in the region.”

Be First to Comment